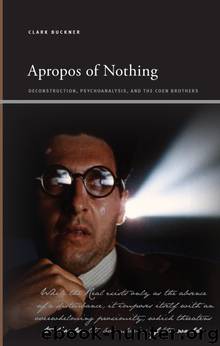

Apropos of Nothing by Buckner Clark

Author:Buckner, Clark

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: State University of New York Press

Published: 2014-11-18T16:00:00+00:00

The Plural Logic of the Aporia

Although Derrida’s philosophy essentially derives from the project initiated in Heidegger’s early existential phenomenology, precisely as testimony to this debt, Derrida brings the force of Heidegger’s thinking to bear on his own work: both by criticizing his continuing direct overvalorization of self-presence, and by critically redoubling the negativity in his concept of the differential underdetermination of identity. In the critiques of Heidegger to which he returns throughout his career, at different junctures, Derrida thus takes contrary tacks. In his 1968 paper “The Ends of Man,” for instance, Derrida argues that despite the force of his critique of the purportedly self-transparent subject of modern philosophy, Heidegger continues to presuppose the fundamental unity of man in the privilege he grants to self presence in Dasein’s reflexivity as the being for whom its being is a question. Derrida thus brings Heidegger’s own critique of objectivism to bear on Being and Time, pressing it further “in the same direction” by arguing that Heidegger does not sufficiently realize his own stated project. In the essay “Ousia and Gramme,” however, Derrida critiques Being and Time “in the contrary direction,” by arguing that the possibility of articulating the ontological difference remains irrevocably qualified by the objectivism that it aims to subvert. He writes, “What if there was no other concept of time than the one that Heidegger calls ‘vulgar’? What if, consequently, opposing another concept to the vulgar concept were itself impracticable, nonviable, and impossible?” (Derrida, 1982b; 14).

In his 1993 book, Aporias, Derrida brings both these strategies to bear specifically upon the question concerning the fate of anxiety in deconstruction, through a sustained meditation on the intersection of death and language, which not only affirms Heidegger’s concept of being-towards-death, despite subverting its decisive determination, but, still more fundamentally, radicalizes Heidegger’s concept of the impossible possibility of death in his own concept of the aporia of the impossible. Orienting his reflections, Derrida asks, “Is my death possible? Can we understand this question? Can I myself pose it? Am I allowed talk about my death? What does the syntagm ‘my death’ mean? And why this expression, ‘the syntagm “my death”’?” (Derrida, 1993; 21–22).

Addressing these questions, Derrida first juxtaposes Heidegger’s existential analytic and the histories of death written by Philippe Ariès and Michel Vovelle, arguing that these discourses entail “an irreducible double inclusion,” in which each both presupposes and entails the other (Derrida, 1993; 80). Studying the diversity in cultural practices related to death and dying depends upon a definition of death that is beyond the scope of the historian’s discipline. Indeed, how would one define death as a subject of social, historical investigation? On the one hand, death is elusive: the limit of experience, never manifested directly in experience. On the other hand, death is so fundamental to the human condition that it leaves no field unmarked. If death is the explicit concern of medicine or religion, for instance, is it not also integral to law, to love, to art, to engineering, to war, to education? Death is nowhere and everywhere.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Aircraft Design of WWII: A Sketchbook by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation(32192)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31251)

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(20351)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18811)

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18504)

Shoot Sexy by Ryan Armbrust(17637)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17314)

Portrait Mastery in Black & White: Learn the Signature Style of a Legendary Photographer by Tim Kelly(16933)

Adobe Camera Raw For Digital Photographers Only by Rob Sheppard(16882)

Photographically Speaking: A Deeper Look at Creating Stronger Images (Eva Spring's Library) by David duChemin(16601)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(14496)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14323)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13953)

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13477)

Art Nude Photography Explained: How to Photograph and Understand Great Art Nude Images by Simon Walden(12954)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11709)

The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon(8862)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8791)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8767)